The global voice of the Americas has been represented mostly, if not always, by a dominant Westernized society. Since the Spanish arrival, the consequence of such an encounter as it was in 1492 has left many scars on the land and the people, both physical and psychological. Since then, the indigenous people of the Americas have shown resilience and resistance to disappearing physically, spiritually, and mentally.

The global voice of the Americas has been represented mostly, if not always, by a dominant Westernized society. Since the Spanish arrival, the consequence of such an encounter as it was in 1492 has left many scars on the land and the people, both physical and psychological. Since then, the indigenous people of the Americas have shown resilience and resistance to disappearing physically, spiritually, and mentally.

Dreadfully, colonialism has a strong hold on the narrative of our lives. The Colombian people see it, hear it, feel it, and, without thinking, perpetuate it. Standards of beauty, the practice of religion, the role of art in society, and how we perceive people’s actions to classify them as either backward or progressive are all funneled through the lens of the colonial mind. In Colombia, as well as most of the Americas, western ideologies and practices have been the norm for hundreds of years. This has led to the misconception that indigenous people and our culture are either stagnant in time or frozen in the mystical mythology of the noble savage.

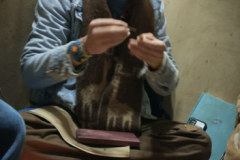

I contend that history does not follow a straight line but is a large tapestry of interwoven threads, overlapping designs, complex craftsmanship, and, most importantly, a work in progress. The importance of pursuing this artistic project has directly to do with combating the ill legacies we inherited from the past. Such as the result of King Charles III of Spain banning the practice of our native language in the year 1770. Two hundred and twenty-one years later, this ban was lifted in the new Colombian Constitution of 1991. The rewriting of the constitution now gives Indigenous people autonomous rights to education, religion, and government. Two years after I was born, my native language became legal. Due to this ban lasting more than two centuries, my Muysca[1] language had become officially extinct, according to scholars, books, and, of course, Wikipedia. However, the language remains alive within us, in our names, the territory we live in, and the memory of our elders. Muysccubun[2] means the "language of people." It is not only the language that we are rebuilding and maintaining orally but a world view and the record of our presence.