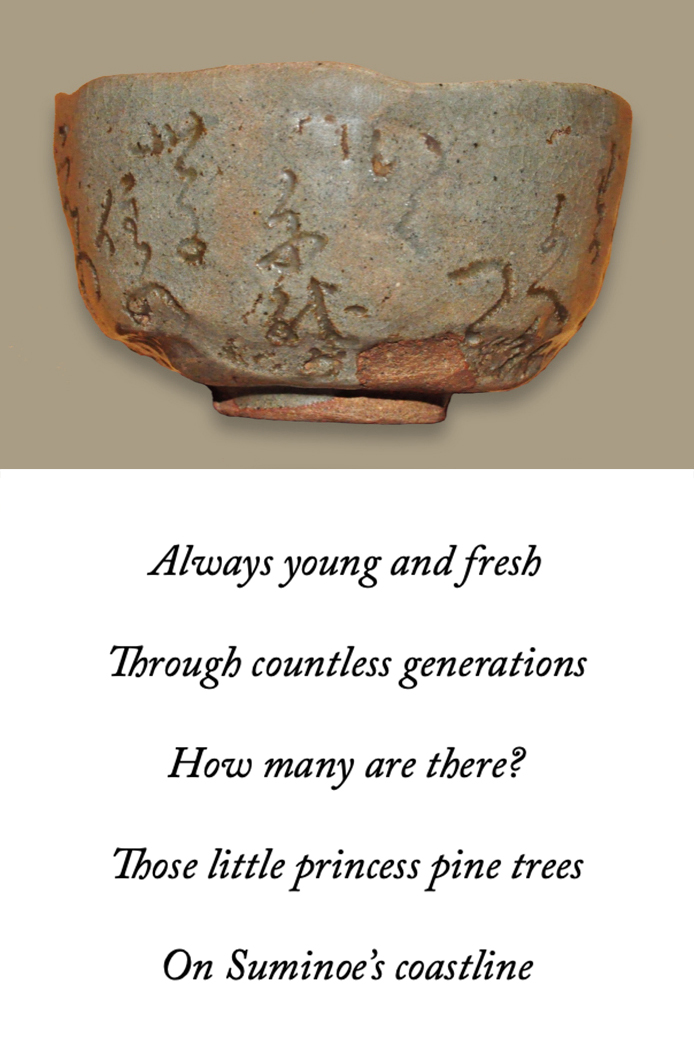

The nun-potter Ōtagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875) is widely considered to be one of Japan’s most remarkable women. Along with emperors, military leaders, and notable men of culture, she is among those portrayed in Kyoto’s Festival of the Ages (Jidai matsuri) each autumn. Despite her preliminary objections, collections of her poetry were published during her lifetime, and countless people in the Kyoto region visited her little hut to pester her for examples of her pottery and calligraphy. Today, her work graces the collections of museums around the world, and homage pieces, copies, and fakes of her ceramics continue to be made, just as they were when she was alive. Her life and work also continue to inspire generations of poets, craftspeople, and followers of Buddhism and women’s rights worldwide.

Rengetsu, whose name means “Lotus Moon,” lived a complex, tragic, yet inspiring life. Although she was born to a woman of pleasure in the ancient capital of Kyoto, her father was a major military attendant to the lord of the Iga Ueno domain, and made arrangements for her care. He saw that she was adopted into the family of a man named Ōtagaki Teruhisa, who he set up as a priest at the Chion-in, a major Buddhist temple. Teruhisa saw to it that young Rengetsu (then called Nobu) received training in skills such as literature and poetry, as well as the teachings of Buddhism. When she was only eight, Rengetsu was sent to train to be a lady-in-waiting at Kameyama Castle in Tanba province near Kyoto. This may have taken place at the order of her birth father, who perhaps wanted her to be raised in a warrior-class setting.[1] During the nearly ten years she spent at the castle, Rengetsu learned formal behavior for women of the samurai class, several forms of martial art, calligraphy, tea ceremony, flower arranging, and dance.

Rengetsu, whose name means “Lotus Moon,” lived a complex, tragic, yet inspiring life. Although she was born to a woman of pleasure in the ancient capital of Kyoto, her father was a major military attendant to the lord of the Iga Ueno domain, and made arrangements for her care. He saw that she was adopted into the family of a man named Ōtagaki Teruhisa, who he set up as a priest at the Chion-in, a major Buddhist temple. Teruhisa saw to it that young Rengetsu (then called Nobu) received training in skills such as literature and poetry, as well as the teachings of Buddhism. When she was only eight, Rengetsu was sent to train to be a lady-in-waiting at Kameyama Castle in Tanba province near Kyoto. This may have taken place at the order of her birth father, who perhaps wanted her to be raised in a warrior-class setting.[1] During the nearly ten years she spent at the castle, Rengetsu learned formal behavior for women of the samurai class, several forms of martial art, calligraphy, tea ceremony, flower arranging, and dance.

In 1807, Rengetsu left Kameyama Castle and returned to Kyoto to marry. Her adoptive father had arranged for her to marry his adopted son, Mochihisa. While in Kameyama, both Rengetsu’s adoptive mother and stepbrother passed away. Her first son, born less than a year after her marriage, also died at only a few weeks old. Her second child, a daughter, died at age two, and several years later, in 1815, her second daughter passed away only days after birth. Rengetsu and Mochihisa separated soon after, and Mochihisa himself died that same year.